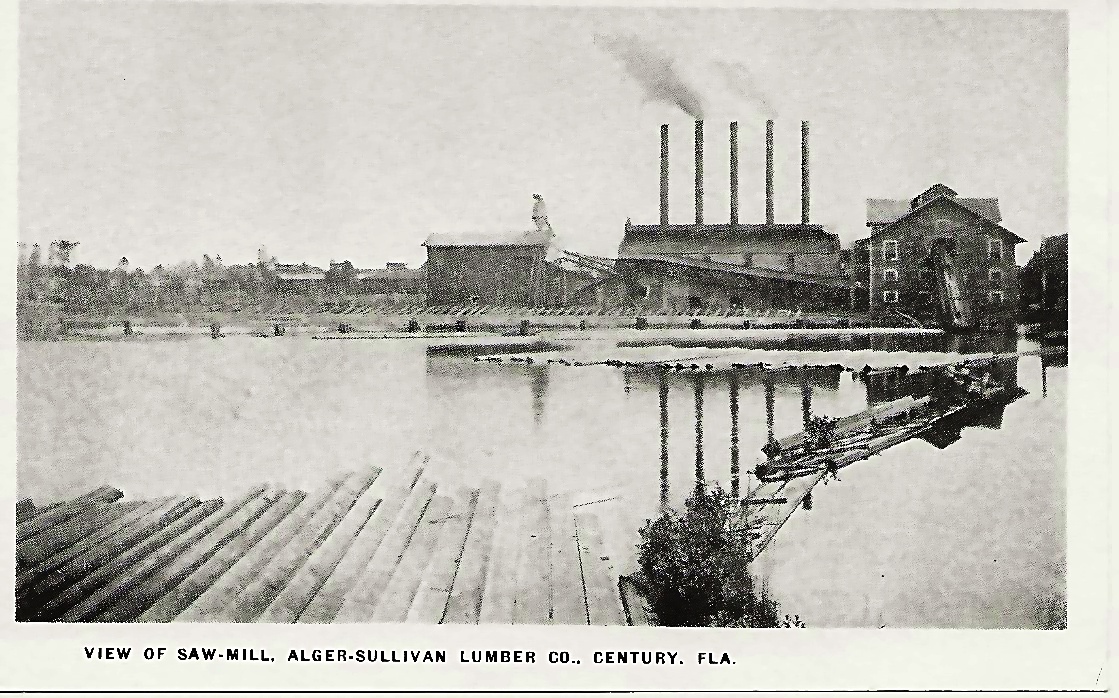

Some thirteen years ago I had some correspondence with a fellow Centurion (someone from Century, Florida), Jerry Simmons, of the Alger-Sullivan Historical Society (ASHS) about the unique personalities and circumstances that combined to eventuate the town of Century, Florida, and the extraordinary Alger-Sullivan sawmilling operation – reputed in its day to be the largest anywhere East of the Mississippi River – that both built and sustained it for two-thirds of a century, but, for a variety of reasons, we never published our findings. Then, just yesterday, Neal Collier, currently a leading light in the ongoing efforts to preserve and acknowledge the fascinating history of the place, posted a note about one of those founders, W. D. Mann, which reminded me that I had already done much research on both him and his associates that I had not shared, so I sent this info to Neal who requested that I find a way to make it public, and as I realized that’s what this blog is for – to share information and interests with all of you – I decided to post it here.

If you find the history of the Florida panhandle, or early American forestry, or even the story of how the Civil War both skewered and served those it affected long into the next century, you might find this of interest. And, if you’re a Centurion, yourself, or simply interested in the history of southern sawmilling, I’m sure you will. Posted with a great affection for this little place where I grew up and the people at its heart. 10/24/2025

Dear Jerry,

When you mentioned you might want to publish my higgledy-piggledy notes sent to you on Facebook about the founders of Century, I was inspired to keep digging till I got to the bottom of the story on every possible front. As you know, when last I wrote you, I was still trying to figure out the Daniel Sullivan part, and now I believe I have the whole thing. It’s an unbelievable tale that really belongs in a novel, but since I don’t have enough time to do that, I’m just going to send you what I have uncovered, as best I can, in narrative form, without references, though I did find strong evidence in every case here presented.

In putting this together, I found Ancestry.com to be especially useful, and I created family trees for the Sullivan brothers, the Hausses, the Heckers and the Henry Glover families, and these were instrumental in taking me to places I could never have imagined. The story turns out to be much more intertwined than I had ever suspected. If you like, I can get you the link to these family trees to look for yourself and for the benefit of the Historical Society.

We all know the main players: General Russell Alger, Daniel and Martin Sullivan, Colonel Frank Hecker and W. D. Mann. To this, I would now add two additional names: Kate Grant Sullivan (Mrs. Martin) and Emily Cropp Sullivan (Mrs. Daniel). Since E. A. Hauss and Henry Glover were both recruited to run things by the founders, they are secondary to the story, but no less important, of course, to the history of our town.

I have always been curious about how Alger-Sullivan happened, and even made an appointment with Mr. Hauss when I was in Mrs. Coleman’s fourth grade class studying Florida history to interview him on the early years. Of course, when I was 10, I didn’t know what questions to ask, and even if I had, I’m not sure he would have answered them.

Unfortunately, it’s not a short story because to really understand it all, you have to start at the very beginning, and it also has to be broken into its two halves: the Alger story and the Sullivan story, which both, ultimately, come together when W. D. Mann shows up in Mobile in 1866 and brings them together.

THE SULLIVAN SIDE OF THE STORY

There were carpetbaggers, and then there were benevolent opportunists who descended on the South after the war. The scalawag types saw a wounded country and swooped in to take advantage, but there were also others who, while certainly looking to do well for themselves, were also motivated by some larger calling, a greater good. W. D. Mann was the ultimate rapscallion, but the Sullivan brothers, who came to this country as children only eight years before the Civil War and had no true allegiances except those which were the inevitable result of their having been drafted into the Union Army, were looking for a place where they could practice their devout Catholic faith and put their considerable energies and penchant for prosperity to good use. That said, they got very little credit for their good works from the natives, who would not readily forget that they had both served in the Union Army, but I’m getting ahead of my story.

KATE GRANT of Stella Plantation

There are so many great stories to tell, that it’s hard to know where to start, but I could hardly do better than the tale of Kate Grant, who dropped her pretentious given name, Catherine Clemence Grant in her youth, and as far as I could find, never used any other name but Kate for the rest of her life. The threads of her story really begin when Mademoiselle Genevieve Dulat was wed to the noble Don Antonio de Gras in the Cathedral of Our Lady of Sorrows, now the Cathedral of St. Joseph, in Baton Rouge on January 15, 1773. Don Antonio, from Majorca, was one of the earliest settlers in the Baton Rouge area, which, unlike New Orleans, was ruled by the Spanish king since the westernmost part of Florida reached all the way to the Mississippi River until 1810. Don Antonio helped design and lay out the city of Baton Rouge and personally donated the land for the Cathedral. His wedding to Genevieve was the very first to be celebrated in the newly consecrated building and he built their home just north of the present church where the State Capitol Annex now stands.

The marriage was a clever one for the Spaniard, who, as a recent immigrant, needed “old-money” connections if he was to be accepted in the highest levels of New Orleans society and his new bride could not have been more well-placed. She was the perfect combination of early Louisiana influences including both German and French. Her mother was a third-generation full-blooded German immigrant whose forebears had arrived in the Colonies in the mid-1600s, and her father – a true Acadian – was a fourth-generation full-blooded Frenchman (except for 12.5% Native American that resulted from his Huguenot grandfather’s scandalous marriage to a Mic-mac princess in Nova Scotia before emigrating with the most of the “Cajun” population from Canada to the New Orleans vicinity in the early 1700s.)

As far as I could determine, Don Antonio and Genevieve only had one child, Joseph Grass, who also married well, choosing Clemence Arthemise Broussard, also a fifth-generation American on both sides of her family (her mother’s family name was Molaison). And, in 1827, their daughter, Olympe Clementine Grass was born.

Only a few years earlier, in 1820, another immigrant, this one from Scotland, had arrived in New Orleans. His name was Alexander Grant, and he is listed as a “merchant” on many documents, but it seems clear that he was a major player in the slave trade. The circumstantial evidence is strong that he was descended from the proprietor of Alexander Grant & Company of Glasgow, which was one of England’s primary slave trading corporations until 1807, when it went bankrupt as a result of the abolition of slavery in that country. The infamous slave fort off of the Ivory Coast was built by Alexander Grant & Company of Glasgow (where our Alexander Grant also hailed from) and there was a different Capt. Alexander Grant, a generation older than ours, who died at sea en route from Barbados to Scotland in 1797 aboard a slave-trading ship. To add to the inference, there was an actual 690-ton slave-trading sloop named the SS Alexander Grant, and, finally, after much searching, I even found an old newspaper ad from around 1830 listing our Alexander Grant as the agent for a slave “estate sale” to be held in New Orleans.

Whatever he did, Alexander Grant made lots of money, because, in 1845, he purchased the immense Stella Plantation just south of New Orleans on the Eastern bank of the river. (You can type “Stella Plantation” into Google Earth and it will take you right there since it is still being operated, these days as a weddings and event venue that takes advantage of the elegant, enormous plantation house and expansive Mississippi River frontage.) It was a massive sugar plantation with scores of slaves and since sugar cane was primarily exported to trade for slaves, his purchase makes perfect economic sense. It is also possible that he saw it as a way to hedge his bets, as the abolitionists were gaining ground by the time he bought the plantation and he may have decided to have a sweet insurance policy, just in case. Slaves or no slaves, sugar would always be in demand.

Alexander Grant married a woman named Julia (last initial D) from Virginia, but that is as much as I have been able to dig up on her background. In 1820, she bore him a son, whom they named Alexander Grant, Jr. He grew up in his father’s footsteps – at least the maritime part – and became a river boat Captain on the Mississippi, his last vessel being the SS Captain Quitman, which was still in service during the first year of the war, but was burned in 1862 to prevent Admiral Farragut of the Union Navy from capturing it when he overran New Orleans. (Alexander Grant, Jr. then enlisted in the newly-formed CSA Navy as a Lt. and served aboard the CS Missouri, a Confederate Ironclad, until it was decommissioned at the end of the War.)

Several years before the war, in spite of his “newcomer” status and the somewhat off-putting business of his father (slave traders were never considered a very reputable bunch, in spite of the strength of their business), Alexander Grant, Jr. had made an outstanding match for himself when he managed to persuade none other than Olympe Grass – veritable New Orleans royalty – to become his bride. Of course, as a river boat captain, he was away from home most of the time, so Olympe and her growing brood of children – ultimately they had four – lived during the 1850s and 1860s on the Stella Plantation with her in-laws, and who wouldn’t. It was about as good as Southern plantation life could get. It is hard to say upon whom Margaret Mitchell may have based her depiction of Katie Scarlet O’Hara, but the life lived by Katie Grant was as charmed, if not more so, at least, until the Yankees came.

In 1851, Olympe and Alexander Grant, Jr. had their first child, our heroine, Catherine Clemence Grant, or, simply, Kate. In 1873, she would change her name once more, for the last time, to Mrs. Martin H. Sullivan.

EMILY S. CROPP of Barbour County

The story of Emily Cropp also begins in the middle of the 18th Century, since it was about 1750 when her great-grandparents, Mordecai and Esther Cohen Myers, and his brothers-in-law, Abraham and Solomon Cohen, became the first Jewish Settlers to set up shop in George Town, SC. George Town, now Georgetown, was just up the coast from Charlestown, but boasted an economy based upon indigo and rice plantations, rather than the slave/cotton/privateer economy of her larger southern neighbor. Mordecai and Esther had eleven children in all, seven boys and four girls, and they all did well for themselves. Moses Myers was the first Jewish attorney in SC, being admitted to the bar in 1793 at the age of 21. He also served as Clerk of Court of the Common Pleas for 10 years. Jacob, his brother, was a blacksmith, postmaster, and captain of the local artillery company. Abraham Myers was also a lawyer, being admitted to the bar three years after his brother and was elected Mayor of George Town for two terms, and Levi Myers, his younger brother, received his medical degree from the University of Glasgow in 1797 and was the first Jewish doctor to belong to the Medical Society of SC. He enjoyed a distinguished career as a doctor in the low country, mostly in Charleston, until a hurricane in 1822 swept his house out to sea, drowning his entire family. The other three boys were Solomon, Isaac and Cohen Myers, and it is either Solomon or Cohen Myers who concerns us here.

In 1875, one Capt. Abram Huguenin of the CSA, took the time to write down all his recollections of his family history, which is good for us, because the only thread that links our story to that of the Myers family is this passage: Anne [Huguenin, his first cousin] married Myers (Col.) of Savannah, Ga. I have heard my father say that he heard from his father, that he (Myers) was a very fine fellow, of great humor, he died young, leaving two daughters, one of which married Longworth and was drowned in the “Pulaski” (steamer), the other married Benjamin Cropp and has a large family in Alabama.” Now, by process of elimination, I have been able to determine that the only possible candidates for this “Myers (Col.) of Savannah, Ga” are Solomon and Cohen Myers. Also, since none of the Myers sons was ever a Colonel in any army (they were too young for the Revolutionary War and just right for the War of 1812, but no Colonels), I believe the “(Col.)” was mis-transcribed from the originally handwritten history and he was either writing “Sol.” or “Coh.” It could be either one. Isaac lived a long life, so it couldn’t have been him, and the other four mentioned above are all accounted for with families of record.

So, Anne Huguenin married one of the Myers boys, and they had two daughters. One of them drowned with her husband when the SS Pulaski sank, and the other, Louisa Caroline Myers, born in 1796, married a Georgia preacher named Benjamin Cropp, who then moved with her to Barbour County, AL sometime in the early 1800s.

But that is not all there is to this story, because there was another claim to fame in the Myers clan. Abraham Myers, who had been mayor of Charles Town, and his wife, Belle Nathans, had a son in 1811 whose name was Abraham Charles Myers, who put his talents to work for the young United States by serving in the Quartermaster Corps. His grandfather Mordicai in George Town had supplied the Continental Army throughout the Revolutionary War, including Francis Marion, the Swamp Fox, as he raided the British in and around the low country, so supplying military operations was something long instilled in his blood. By the time the War Between the States began, young A. C. Myers had been graduated from West Point (1833) and was already a senior officer in the U.S. Army Quartermaster Corps, so Jefferson Davis wasted no time in appointing him as the first Quartermaster-General of the Confederacy. A. C. had already set up housekeeping in New Orleans, his adopted city, and he continued to operate from there until Admiral Farragut took over the city, at which time he moved to Montgomery, and from there to Richmond as the War progressed.

One can only conjecture whether or not Louisa Cropp visited her cousin in New Orleans, but it would seem entirely likely. And, if she did, she would surely have taken her grown daughters, including our second heroine, Emily S. Cropp, with her. In other words, even long before they each married a Sullivan brother, they might well have been acquainted through their New Orleans connections. But, either way, marrying into such a well-structured commercial network as that of Quartermaster-General Myers was a real coup for the Sullivans. (For what it’s worth, Fort Myers, FL is named after Daniel Sullivan’s mother-in-law’s first cousin, A. C. – not bad.)

DANIEL FRANKLIN SULLIVAN and MARTIN HENRY SULLIVAN

On March 7th, 1853, the SS DeWitt Clinton steamed into New York harbor. On board were Patrick Sullivan, listed as a farmer on his immigration papers, his wife Bridget, and their six children Catherine, 19; Daniel, 16; Bridget, 11; Martin, 9; John, 7; and Ann, still in diapers. I have not been able to find where, exactly, they settled, but it seems to have been in or near the city since, once the War was joined, Daniel and Martin were drafted into the Union Army in New York City. Both signed on with the 88th New York Volunteers, called the “Irish Brigade” because it was almost exclusively made up of Irish immigrants. Daniel was mustered in on the 19th of September, 1861 and when Martin turned 18 on February 1st of 1862, he joined the same brigade, though in a different company.

Most of the Irish Brigade was sent to Washington to join the Army of the Potomac and the list of battles it fought paints a long, slow, deadly trail from the early days of the war right through to the surrender at Appomattox Courthouse, and Daniel was among this group of soldiers. He served for his full term before being mustered out in good condition exactly three years, to the day, from when he had begun.

Martin, on the other hand, was fortunate to be in one of the two Companies of the 88th who were assigned to guard Fort Washington in the Bronx, so he was still in New York when he was placed on the disabled list in late November, only 10 months after he started, with an unspecified bowel ailment. He must have improved, however, because in June of ’63, while working in the city as a bartender (now age 20), he re-registered for enlistment with the Army, but I could find no record of his having served a second tour of duty.

Daniel’s final action as a soldier was at Reams Station, VA, a few miles south of Richmond, in August of 1864. The only hard information, such as it is, that I have found about his movements and actions from September 19 until he marries Emily in 1868, can be found on the Pensapedia website, where it says that he supplied the Union Army by rounding up free range cattle. However, we know enough about him to connect some dots and fill in the blanks.

We can begin by assuming his first priority would be to get home to his family, who were still, as far as we know, in New York City where his strapping brother was bartending, passing through Washington before taking a train north. With three years under his belt as an ambitious soldier in and around D.C. to make contacts and explore possibilities for making his way after the war, he most likely already had a plan in mind and he wasted no time putting it into motion.

It is not a well-known fact that Florida, in those years, was grazed from one end to the other by hundreds of thousands of freely-roaming head of cattle, and they were especially thick in the panhandle, having grown and multiplied ever since 1540 when “Don Diego Maldonado brought a large herd of Spanish cattle and horses to the Pensacola Bay area to supply the expedition of Hernando De Soto. Don Diego was unable to make contact with the conquistadors and it was reported that many of the cattle were lost to run wild in the timber of north Florida” (from Florida-Agriculture.com).

During the War between the States, it was well known that the great “wild” herds in central Florida were one of the Confederacy’s most valuable food resources – indeed, it was famously a thorn in the side of the Union – with most of that beef flowing out of Tampa Bay or being driven by sympathizers north to the Georgia and Alabama borders for distribution to the forces. And, since we can assume there were similar herds of roaming cattle on the Union-held timberlands in and around Pensacola at the time, no doubt the Union was eager to get in on the free food at its feet and looked for a way to round up as much of this untapped resource as possible.

“What?” I can just hear Daniel, whose first 16 years had been spent enduring the Irish Potato Famine, saying when he heard about this. “Are you telling me there are free cows just roaming around down there for the taking? You mean I can serve my country and make a fortune just by grabbing my brother and heading for Pensacola? What are we waiting for?!”

Now, the difficulty, and reason these cattle had not already been confiscated, lay in the fact that the only possible way to get them from isolated Pensacola (the Confederates having completely taken up and removed the rail lines as they left) was by ship, and the loading docks and facilities had been ransacked just like the railroads when the town was abandoned by the Confederates. But where others saw obstacles, Daniel and Martin saw opportunity, and they set out to make it possible to load the cattle and sail it to New Orleans, the nearest Union-held port that could get it to the inland armies. The enterprise would also have required their setting up business on the receiving end, so it seems clear that both cities would have seen a lot of the Sullivan brothers once they began.

In other words, as best I have it figured, Daniel and Martin left New York City by the end of 1864 and sailed south, around the Union-held fortifications at Key West, and most likely landed in Pensacola just in time to begin work around the first of 1865. The very nature of the job they had to do would have taken them deep into the unspoiled timberlands at least as far north as they could go before running into Johnnie Reb, introducing them to the extraordinary value in the towering trees that grew all around, untouched and under-appreciated. With government gold to spend, they would have had all the resources they needed to corral their cattle, and since the freight docks had to be rebuilt and outfitted – another opportunity! – Sullivan’s Wharf, which would be the foundation for all their later successes, was soon under construction. Perhaps, while Daniel stayed in Pensacola to run things, Martin accompanied the shipments back and forth to New Orleans to make sure they were properly recompensed for their troubles (which would also have given him ample opportunity to get to know and love the woman he would marry eight years later).

And what a place they would have found when they arrived in Pensacola! It would be hard to imagine a more desolate or unwelcoming sight. It was deserted, destroyed, dilapidated and dirty; home to squatters, ne’er-do-wells and reprobates who, for whatever reason, were not serving either side in the war – the human flotsam and jetsam of its tides.

It was deserted because, when the Union forces took over the city in May of 1862, the retreating Confederate soldiers burned every government building they could, destroyed anything that might be of value to the Union, and all of the locals who were Confederacy sympathizers headed north into Alabama, leaving only the Union loyalists in place when the U.S. Navy moved in. For a few months, the better homes and gardens of Pensacola provided luxurious barracks for the Union officers, but then they were ordered to desert what was left of the burned out city and reposition themselves behind the rebuilt fortifications at the navy base, taking all the locals who were Union sympathizers with them for their protection. This made for cramped and uncomfortable living on the base and left the city open to “feral” invaders and, astonishingly, the result was that by early May of 1863 there was one – one! – permanent resident left in all of Pensacola, and that was the Spanish Consel, Francisco Moreno, who, as it turned out, was a Confederate spy, which may explain his willingness to remain there all by himself.

And, it was onto this wasteland that Daniel and Martin Sullivan disembarked. It must have taken their breath away when they saw the daunting challenges they faced, but they were full of energy, drive and determination, and, finally released from the bonds of poverty and war, they must surely have been chomping at the bit to make their mark on the world. Where others saw disaster, they only saw possibilities, and they intended to make the most of them.

Of course, their enterprise for the Union armies could have only lasted for a few months, since the War was over that spring, but if there were still free cattle to be rounded up among the pines trees (free-range cattle in Florida went extinct around the turn of the 20th Century), I’m sure they worked it till the supply was exhausted. By then, of course, they had their wharf, their New Orleans connections, and enough of a nest egg to parlay into a remarkable series of successes. And, while the details are lost to history, somewhere along the way Daniel, supplier of the Union Armies, met and, in 1868, married – ironically enough – the beautiful and accomplished cousin of the Quartermaster-General of the Confederacy and great-granddaughter of the man who had supplied the Carolina Revolutionaries. By all accounts she was a remarkable wife and mother and a great asset to Daniel. In an obituary published in the New Orleans Times-Democrat following his death, it says he was “Blessed with a wife whose angelic goodness and truth surrounded her with a halo and placed her on a pinnacle far above ordinary women.” Even allowing for the hyperbole of the Victorian era, that’s quite a compliment.

Emily Cropp Sullivan bore Daniel two daughters. Mary L. was born in 1869 and Kate in 1871. This latter name and date are instructive, since it was two years before Martin married Kate Grant in 1873, leading one to postulate that she and Emily may well have been good friends and it was that connection which led to Kate’s courtship with Martin in those years.

Quickly, the brothers began to make the most of the opportunities that surrounded them on every side. They had the wharf and needed something new to export, and since the only local, exportable resource of any size was held in the vast pinelands that lay to the north in Escambia and Santa Rosa Counties as well as for miles into the southern counties of Alabama, they set about, in a determined and systematic way, to bring that resource to market. They bought up every bit of the forest that became available, bought or built the saw mills required to process them, and laid new railroads into the interior to bring those logs to market.

As more and more money, almost all of it generated by the timber industry, flowed into the area, the brothers launched the First National Bank of Pensacola to keep it safe, and, as the general prosperity of the area grew even further, they capitalized upon the dearth of cultural diversion in the area by constructing the Pensacola Opera House, which was played by all of the great international touring artists of the latter quarter of the 19th Century from Caruso to Sarah Bernhardt, all of whom, presumably, were personally feted by their hosts.

By 1873, Martin had convinced Kate Grant to be his bride, and finally the equation was complete. Through Emily Myers Cropp, Daniel had family connections that spread throughout the whole of the Eastern Seaboard, and through Kate, Martin’s family reach extended into the pockets of the entire Western half of the United States, beginning with New Orleans, itself. The boys were set, and what a remarkable ten years they must have enjoyed as each of their enterprises seemed to only grow into more and better enterprises. They had their forests – a seemingly inexhaustible resource in those days – to harvest, their wharf to ship their product to market, their bank to keep their earnings safe and gaining interest of their own accord, and their opera house to keep them diverted and provide free entertainment for themselves and all their distinguished visitors from the ends of the earth.

In ’74, Martin and Kate welcomed Marie, the first of their seven children. Julie was born in ’75, Daniel Francis Sullivan, II, in the Centennial Year, and Martin H. Sullivan, Jr., in 1879. Their fifth child, Charles, came along in December of 1884, but he would be the first never to know his Uncle Daniel, because he had died six months earlier, in June. It was sudden, and I have not been able to find a cause of death, but Yellow Fever epidemics spread by mosquitos were an annual affair in those days, and since he died in the summer, that is one possibility. In any event, he went out in a burst of productivity. In only the last three years of his life, he executed more than 300 contracts for tracts of forestland – from 120 to 1200 acres each – in Alabama alone. There may have been more in Florida, as well, as evidenced by the mills and railroads the Sullivans built throughout the Western Panhandle, but by the time he died, he had increased his land holdings to as much as a quarter of a million acres. Aside from a few specific bequests, the administration of his estate was entirely vested by his will in the care of Emily and Martin, to do with as they saw fit, and, overnight, Martin’s reach and economic wherewithal went from considerable to commanding.

There seems to have been a peculiar conspiracy of silence surrounding the Sullivan brothers in those early years. If you go through the extraordinarily detailed timeline of Pensacola history on the PNJ website, the most remarkable thing is that nothing whatsoever is listed there between the day the city was surrendered to the Union in May of 1862 and when the war ended in April of 1865. Nothing. Not anything at all is considered to have happened during those years. I further found it curious that in a Master’s thesis I read that tells the Pensacola story during those and the reconstruction years in great detail – including many pages on the timber resources and marketing – the name Sullivan is nowhere mentioned. Only those who were native to the area are included as having been instrumental in these matters in those times. Since I don’t believe the writer of the thesis would have had any intent to “smear by omission” by leaving them out of a scholarly paper written fully 150 years after the fact, I can only presume that, in all the considerable research he did, there just wasn’t much mention of the Sullivan brothers in the local historical records. Yes, they may have come in from the north, and yes, they may have profited by taking advantage of the ripe opportunities they found in Pensacola, but they did it by the sweat of their brows and the clarity of their business acumen, not by conniving and subterfuge, so while the locals of the time may have seen them as carpetbaggers, I don’t count them as such. They did not immigrate to Pensacola to pillage, they came to apply themselves and make a living by filling a perceived need and working hard, and in so doing they created much of the infrastructure upon which the new Pensacola was built; the very foundation for whatever prosperity the area enjoyed in the years that followed.

It is also telling, I think, that the only obituary of Daniel that I have been able to find, though it was published in the Pensacola Commercial, was a reprint of one written and published the day before in New Orleans. No one in Pensacola seems to have been interested in extolling the virtues of a man who had done more than anyone to resurrect prosperity in his adopted city. I think he really loved Pensacola, and he seems to have put his money where his heart was in many ways. Of course, I’m sure he always made a profit so it’s hard to feel sorry for him. I’m convinced it was because of the cold shoulders they must have endured that he (or maybe it was Martin’s doing) made sure he would not be forgotten for generations to come by purchasing a huge plot in St. Michael’s Cemetery and erecting the tallest, most impressive monument there. Even today, it strives to say: this was great man.

The obituary, signed by “R. M. K., New Orleans Times-Democrat” and published in Pensacola on June, 18, 1884, reads:

“The sad intelligence of the death of Daniel F. Sullivan at his home in Pensacola, Florida, has by this time been telegraphed to all the principal cities of Europe and America and in each of them warm and true hearts are today mourning this sudden ending of a life so noble, so pure, so [unclear], with work well done and character wisely and generously bestowed.

“A typical Irish gentleman, Mr. Sullivan possessed those qualities of mind and heart which commanded the respect and won the esteem and regard of all who knew him.

“His wonderful business talent was known all through this country and is vouched for by the success of his numerous and varied enterprises. By his untiring energy he soon amassed a large fortune and in an incredibly short space of time was justly numbered among the merchant princes of the South.

“Generous and just, he was ever willing to aid the poor and deserving. No young man anxious to work and struggling to gain an honest livelihood ever applied to Mr. Sullivan in vain, and the different branches of his life work gave employment to hundreds who feel that thy have lost their best friend.

“Gifted with a genius for acquiring wealth, he gave with untiring hand to the poor and needy. The blessing of the widow and the orphan sounded daily in his ears. Churches and charitable institutions of all creeds appealed to him, confident of his willingness to aid them. Philanthropy in the best sense of the word. He never wearied of improving and beautifying the city of his adoption.

“It was this writer’s proud privilege to claim him as a friend and to study the simplicity, beauty and worth of his character in that most trying of all crucibles, his home. No truer, tenderer heart ever beat in the breast of man, and no man ever did more for the comfort and happiness of his family.

“Blessed with a wife whose angelic goodness and truth surrounded her like a halo and placed her on a pinnacle far above ordinary women, his home life was indeed enviable and beautiful. To her and to his loving children it is difficult to suggest anything in mitigation of a grief so unequaled. To God, whom they have ever faithfully looked and feared, we commend them, confident that He will help them bear this affliction with which he has seen fit to visit them.”

Two years after Daniel died, Martin’s sixth child, Russell, was born. It was January of 1886, and I also find this instructive since Russell was not a family name and uncommon enough that I suspect General Russell Alger, who had been elected Governor of Michigan in 1884, had already come into the picture, one way or another. This was most likely through their mutual acquaintance, W. D. Mann, who, like the Sullivans, had seen the virtue of investing his considerable fortune in Alabama timberlands, beginning with his arrival in Mobile in 1866, but unlike them, was a true scoundrel.

The last of Martin’s children, John J. Sullivan, would be born in 1887, even as his father’s vast expanse of lands, network of local railroads, bank, opera house and export/import operations continued to thrive. The demand for Southern Longleaf Yellow Pine grew exponentially in the 1880s and ‘90s due to its expanding reputation as a strong, durable wood capable of supporting the vast factories spawned by the industrial revolution across Europe and the Americas. The trees of the virgin forest were enormous – up to 350 years old, 180 feet tall and four feet in diameter – and considered the best to be found this side of Michigan. By the mid-1890s, millions of board-feet of lumber were shipping out of Pensacola every month to supply the needs of governments and business interests around the globe, and all of it from Sullivan’s Wharf.

Indeed, the need was so great, and the ability of the little local sawmills so puny, that something big needed to be done. It was time to build the biggest, most productive sawmill that the best engineers of the time could produce, and to do that, Martin needed a level of world-class expertise that was not to be found nearby. At the time, Michigan was the center of the forest products universe, with the biggest mills and best distribution route, via Lake Michigan, and the lumber industry there was booming as strongly as it was in Pensacola, but on a much grander scale. What Martin needed was an industrialist lumber baron from the North to help him build his dream mill, and who better than the friend for whom he had (apparently) named his fourth son, General Russell A. Alger of Grand Rapids.

THE ALGER SIDE OF THE STORY

Most likely because of his titles and fame, General Alger has always impressed me as being the brightest star in the Alger-Sullivan constellation, but I find that of all the players in the story, he turns out to be the least involved. Nevertheless, he provided exactly the expertise in large-scale lumber milling that was needed, and the people he sent down from Michigan to put it all together – Hecker, Glover and Hauss – proved to be fundamental and were, in the end, the three people who, along with Martin, Kate and Emily, were most responsible for everything that happened in the design, construction and operation of Century and the Alger-Sullivan sawmill for nearly sixty years.

Brevet Major-General RUSSELL ALEXANDER ALGER

40th U. S. Secretary of War, 20th Governor of Michigan, U. S. Senator,

and 23rd Commander-in-Chief of the Grand Army of the Republic

Orphaned at thirteen in Ohio, Russell Alger worked on a farm to support himself and his two younger siblings before teaching for two years, getting his law degree and moving to Grand Rapids in 1860 to engage in the lumber business. He married and had six children and as his fortune grew, so did the prominence of his family. He enlisted as a private at the start of the Civil War and was soon elevated to Captain and then Major in the 2nd Michigan Cavalry Regiment. After several successful battles, in July of 1862 he was named Lieutenant Colonel in command of the 6th Michigan Cavalry. Coincidentally, a year later, a gentleman named W. D. Mann was given the same rank and placed in command of the 7th Michigan Cavalry, both serving under the command of General George Armstrong Custer. They would serve in close quarters for the remainder of the war and were particularly instrumental at the battle of Gettysburg, meriting strong mentions in General Custer’s report on the battle.

Over three years, Alger commanded his cavalry in sixty-six different skirmishes and battles and was, quite coincidentally, mustered out of the army only one day after Daniel Sullivan, on September 20, 1864, and in the same general area. It is quite possible they met for the first time on that occasion, but that is pure speculation.

After the War, Alger settled in Detroit as head of both the Alger, Smith & Company and the Manistique Lumbering Company and personally owned a great pine forest on Lake Huron that covered more than 64,000 acres. (Given that, the 250,000+ acres of the Sullivans must have astonished him.) As Alger prospered and his family grew, he branched out into politics and, in 1884, he was elected Governor of Michigan and served a two-year term through the end of 1887, when he refused to be re-nominated.

In 1897, President McKinley asked Alger to serve as his Secretary of War, and he was in charge for most of the Spanish-American War, which began the next year. He was asked to resign in August of 1899 because the war wasn’t going very well.

Alger was appointed by the Michigan Governor in 1902 to fill out the remaining months of a U. S. Senate term following the death of the sitting Senator, and was elected to his own term beginning in 1903. He served until his death in 1907.

Colonel FRANK J. HECKER

Like Alger and the Sullivans, Frank Hecker had also started with nothing and built an empire by the seat of his pants. The son of Prussian immigrants, he was born in Freedom, Michigan in 1846. In August 1864, at the age of 18, he enlisted in Company K of the 41st Missouri Infantry, but since the war was nearly over by the time he was old enough to join, he worked until 1866 as a clerk in headquarters of the Missouri forces. After the army, he joined the Union Pacific Railroad for two years, worked on several railroad construction projects until 1876, and then took his last job before launching out on his own as superintendent of the Detroit, Eel River, & Illinois Railroad, where he remained until 1879.

In December 1879, he and a partner named T. D. Buhl founded the Peninsular Car Works to make railroad freight cars. Buhl must have been the larger investor since he was President and Hecker was VP/Treasurer. One of their founding Directors was his fellow Michigan industrialist, General Alger. The combination of lumber and rail made a great deal of sense in those days because, until trucks grew large enough for the task, railroads were the only available means of extricating large saw logs from landlocked forests. Indeed, in its heyday, as you know, Alger-Sullivan was running over 100 miles of track in Escambia County, Alabama. In 1884 or 1885, Hecker and another railroad car magnate, Charles L. Freer (of the Freer Gallery of Art which is part of the Smithsonian) bought out Buhl and changed the name to the Peninsular Car Company. Following a merger in 1892, The Peninsular Car Company became the Michigan-Peninsular Car Company and Frank Hecker remained president until 1899.

However, in June of 1898, the US forces in Cuba fighting under Teddy Roosevelt were in trouble and there were not enough ships in the US Navy to supply their needs, so, General Alger, then serving as Secretary of War, enlisted his fellow Michigander and gave him the authority to purchase and charter ships for the transportation of troops and supplies. On July 18, 1898, William McKinley commissioned Hecker as a Colonel of Volunteers, Chief of the Division of Transportation, Quartermaster’s Department. And, until May of 1899, he continued his purchasing and hiring duties, outfitted transports for conveying troops to and from Cuba and Manila, arranged for the transportation of troops by rail, contracting for the movement of Spanish prisoners from Santiago to Spain, and conducting inspections.

Now, while I’m jumping ahead of the story a little here, it sheds a fascinating light on all of this to learn of something that happened in 1904. Theodore Roosevelt had appointed Hecker to the second Isthmian Canal Commission to supervise the construction of the Panama Canal and establish the Canal Zone government in March of that year. “However, in October, newspaper allegations claimed that the Commission purchased construction and other supplies without public advertisement and suggested that Col. Hecker may have mishandled lumber contracts to suit the business interests of his friend, Senator Russell A. Alger, and himself. Col. Hecker resigned the next month, citing illness related to the Canal Zone climate (despite encouragement from President Roosevelt to remain in his position).” [taken from the University of Michigan website] Clearly, it’s a lot easier to ship lumber from Pensacola to Panama than from Michigan, so this undoubtedly must refer to Alger-Sullivan production.

It is also worth mentioning that, in 1898, Col. Hecker’s daughter, Louise May, married Count Julius von Szilassy of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. He would later be made a Baron and died in 1935, but only seven years after their marriage, in 1905, Louise filed for divorce, citing “non-support” as the reason for her decision. They had one son, George Charles Frances Szilassy. An article printed in the June 2, 1905 edition of the New York Times reads:

“COUNTESS ASKS DIVORCE. Former Miss Hecker of Detroit Brings Suit Against Diplomat.

“DETROIT, June 1 – Countess Louise May Hecker de Szilassy, daughter of Frank J. Hecker of Detroit, ex-member of the Panama Canal Commission, has begun a suit for divorce from Count Guyla Hope Joseph de Szilassy of Vienna, who was for many years Secretary of the Austro-Hungarian Legation at Washington. They were married Dec. 23, 1898. The countess charges non-support in her bill. She has one child.”

From May 1905 to December 1906, Col. Hecker and a group of three Michigan friends owned a controlling share of the Detroit Free Press and he was on the original Board of Directors of the Union Trust Company of Detroit, Detroit Lumber Company, and, of course, Alger-Sullivan Lumber Company. He was also a Director on the Boards of the Detroit Copper and Brass Rolling Mills, LaSalle County Carbon Cola Company, and State Savings Bank (later the Peoples State Bank). He also lived longer than any of his fellow “first-generation” founders, and died at home in Michigan in 1927.

HENRY GLOVER

The details of Henry Glover’s life are sketchy, at best, but we do know that he was born in Vermont in 1851 and by the age of nine had moved to a 450 acre farm in Saginaw County, Michigan, rich timber country. When he was 32 he married Elizabeth A. Wilson in Bay City, not far from where his family had first set up their farm. In 1879, their first child, George Ezra, was born, and in 1887, their second, Irene Elizabeth. Since Henry Glover was too young to have served in the War, his youth was most likely devoted to learning the lumber trade which surrounded him on every side. In a Canadian census from Algona, Ontario – literally right across the line from Michigan – in 1891, he is listed as a lumberman.

Sometime after that, but before 1900, he moved his family to Mobile, and there, in 1900, he is listed in the census as the manager of a lumber company. So, while Alger and Hecker must have known of him, at least by reputation if not professional association, his move south must have occurred earlier than the inauguration of Alger-Sullivan and I detect, once again, the fine hand of our old friend W. D. Mann, long removed to New York City by then, but still very active in the region, and still holding some Alabama timberland of his own in the Mobile area.

In any event, there is little doubt that the new Alger-Sullivan Syndicate (the legal name of the holding company formed to own Alger-Sullivan Lumber Company and the associated lands) was well acquainted with Glover and his worth as a lumberman, since they chose him to oversee the construction of the mill and the town that we all know so well.

Unfortunately, Glover died early, in 1911, at the age of 59, so we will never know what contributions he might have made as the company matured. We can all thank him, however, for his greatest contribution to Century, his darling daughter, who was still darling sixty years later, our own Miss Irene.

WILLIAM D’ALTON MANN: WHERE THE TWO SIDES MEET

W. D. Mann was the Rupert Murdock of his age, though he didn’t start out that way. Like all of the other players in this story, he was a self-made man and, at least in the beginning, thrived on his ingenuity and resourcefulness.

Ready to join the war effort but unimpressed with his chances in Sandusky, Ohio, where he was born, he moved into Michigan where he had learned he would be given an officer’s commission if he could round up 1000 soldiers to fight under him. With charm, guile and exemplary salesmanship, he rounded up the quota in no time at all, but was dashed to find that the Michigan commanders felt his recruits were needed elsewhere and gave them to another commander. However, the Michigan Governor was impressed with his industriousness, so he challenged him to do it all over again in Saginaw, where the supply of available men was much smaller, with the promise to give him the command if he succeeded. He did, and on February 9, 1963 was named commanding Colonel of the 7th Michigan Cavalry, serving beside the commander of the 6th Cavalry, Russell Alger.

He also had invented a novel leather ammunition pouch for soldiers to use in the field, and it became very popular because it was configured to hang in the front, thus counterbalancing the weight of the backpacks and making it easier to endure long marches. He sold thousands of his pouches, which is most likely where he got his seed money, and he had amassed quite a bit of it by the time, in 1865, he was named an Internal Revenue Assessor by Washington and sent to Mobile.

Once in Mobile, arriving with a fortune of about $225,000, Mann quickly began investing in local industry, and especially in local timberlands and sawmills. By the 1870 census he was listed as owning $150,000 worth of land and having a personal net worth of $75,000 to boot. That is an enormous amount for someone so young (he was only 25 at the time of his arrival in Mobile) in such difficult times.

By 1870, he purchased a controlling interest in a small Mobile newspaper, and shortly thereafter, when approached by the foundering Mobile Register to invest enough money to keep it afloat, he took control of that paper as well.

In all, he remained in Mobile for about ten years before moving back north. His departure was no doubt occasioned by his involvement in a corruption scheme whereby the newspaper promoted a referendum to agree to the city purchasing a new paving system made basically of treated wooden railroad ties laid like bricks on the ground. It turned out that the timber to be treated for this use was to come from his own lumber interests in the city, and once this was exposed, he felt the time was right to move to New York, where his brother Eugene, who, with similar enterprise, had purchased a failing New York gossip sheet, renamed it Town Topics, and made it the talk of the town. Once he arrived, W. D. took over as editor of the rag while his brother ran the financial end of the company. That arrangement lasted until 1901, when his brothers failing health caused him to move to Arizona and leave the operation of the paper entirely in the hands of his brother.

In 1891, Mann also invented the “Mann Boudoir Car,” a railroad sleeping car, giving us yet another connection between Mann and Hecker. They just keep piling one on top of the other, until it all just seems to have been inevitable.

Perhaps Mann’s biggest claim to fame came in the late 1800s when he famously worked out a deal with the Robber Barons – Rockefellers, Carnegies and the like – not to print juicy gossip about them if they would only pay him a tidy fee for the discretion. Once word of this arrangement got out, Collier’s Magazine ran a big expose, tarnished the image of Town Topics to such a degree that the paper never really regained its former footing.

It is hard to know exactly when, or how, the connections all fell into place between the Sullivans, W. D. Mann, Alger and Hecker, but there were so many overlaps and joint interests in all of their lives, that it would have been more surprising if they had not resulted in some great common enterprise.

EDWARD ADOLPHE HAUSS

Once the Alger-Sullivan syndicate had been formed, and the work was underway to set up what we have all come to know as Century, there were still a few empty slots to fill. Martin Sullivan would continue to play an active role as Chief Executive until his death in 1911, and both Glover and Frank C. Hecker (the Colonel’s son) were also in place to oversee the operations, but there was still the need for a clerk/bookkeeper, and the elder Frank Hecker knew just the man. He was a young, eager and incredibly precise second-generation German who was already making an impression on his superiors at the Michigan-Peninsula Car Company, and he seemed, to Hecker, the perfect choice.

Better yet, he knew before he even asked that he wouldn’t, couldn’t, refuse because the gentleman in question was none other than his sister Anna’s son, little Eddie Hauss.

Once I re-discovered the relationship, that Hecker was Mr. Hauss’s uncle, I seemed to detect a glimmer of a memory that I already knew that from somewhere, but I surely had forgotten it long ago if I did. Of course, when they asked him to come down, they couldn’t have known that by 1911 both Sullivans and General Alger would have died, and the elder Hecker would only arrive from time to time to visit his son in the vast mansion named Tannenheim, leaving only the first cousins – younger Frank C. Hecker and Hauss – to run the place. One has to say they did themselves proud. And, in the end, when the younger Hecker died in 1939, the little clerk from the railroad car company found himself in charge of the whole kit and caboodle. And, there he remained, keeping it as true to its origins as the 20th Century would allow, until it was sold in 1957.

In 1900, just before heading south, Hauss married his Michigan sweetheart, Ethel, and they had two daughters, Anna, in 1904 and Ethel in 1907. Unfortunately, his wife died in the 1930s, and, in 1945, he journeyed to Europe to be married once more, and here, Jerry, is where this story took the most bizarre turn of all, because it turns out that the woman he married and that we both knew as Katalin, was, in fact, the sister of that Count Szilassy who had married, and been divorced by, Hauss’s first cousin, Louise May Hecker, nearly fifty years earlier.

By the way, I looked everywhere for an obituary of Martin Sullivan, who left his interest in the mill operations to Kate when he died in November of 1911, but could find only one short article, in the St. Lucie County Tribune, of all places, and it reads:

“After providing handsomely for all of his relatives in the United States and Ireland, Martin H. Sullivan, the millionaire Pensacola lumberman and banker, who died in Baltimore on October 15 last, by the terms of his will, directs the executors to increase the capital stock of the Sullivan Bank and Trust Company, of Montgomery, Alabama to $250,000. After this is done, he bequeaths his entire holdings in the Montgomery bank to his son, Russell Sullivan.”

Clearly, there is still much to the story, but, at least, I now know to my full satisfaction just how Century came to be, and how it managed to stay that way for so very long.

Hope you are well. Sorry this is so long, but it’s a long story.

Best to you and warm regards,

Tommy Wilson

4/2/2012

© 2025 by George Thomas Wilson